IANS Photo Seoul, (IANS): South Korea on Thursday formally enacted a comprehensive law governing the safe use of artificial intelligence (AI) models, becoming the first country globally in doing so, establishing a regulatory framework against misinformation and other hazardous effects involving the emerging field. The Basic Act on the Development of Artificial Intelligence and the Establishment of a Foundation for Trustworthiness, or the AI Basic Act, officially took effect Thursday, according to the science ministry, reports Yonhap news agency. It marked the first governmental adoption of comprehensive guidelines on the use of AI globally. The act centres on requiring companies and AI developers to take greater responsibility for addressing deepfake content and misinformation that can be generated by AI models, granting the government the authority to impose fines or launch probes into violations. In detail, the act introduces the concept of "high-risk AI," referring to AI models used to generate content that can significantly affect users' daily lives or their safety, including applications in the employment process, loan reviews and medical advice. Entities harnessing such high-risk AI models are required to inform users that their services are based on AI and are responsible for ensuring safety. Content generated by AI models is required to carry watermarks indicating its AI-generated nature. "Applying watermarks to AI-generated content is the minimum safeguard to prevent side effects from the abuse of AI technology, such as deepfake content," a ministry official said. Global companies offering AI services in South Korea meeting any of the following criteria -- global annual revenue of 1 trillion won ($681 million) or more, domestic sales of 10 billion won or higher, or at least 1 million daily users in the country -- are required to designate a local representative. Currently, OpenAI and Google fall under the criteria. Violations of the act may be subject to fines of up to 30 million won, and the government plans to enforce a one-year grace period in imposing penalties to help the private sector adjust to the new rules.The act also includes measures for the government to promote the AI industry, with the science minister required to present a policy blueprint every three years. S. Korea becomes 1st nation to enact comprehensive law on safe AI usage | MorungExpress | morungexpress.com |

Internet shutdowns are increasing dramatically in Africa – a new book explains why (2026-01-10T13:47:00+05:30)

Tony Roberts, Institute of Development StudiesBetween 2016 and 2024 there were 193 internet shutdowns imposed in 41 African countries. This form of social control is a growing trend in the continent, according to a new open access source book. It has provided the first-ever comparative analysis of how and why African states use blackouts – written by African researchers. The book, co-edited by digital rights activist and internet shutdown specialist Felicia Anthonio and digital researcher Tony Roberts, offers 11 in-depth case studies of state-sponsored shutdowns. We asked five questions about it. How do you define an internet shutdown and why do they happen?Put simply, an internet shutdown is an intentional disruption of online or mobile communications. They’re usually ordered by the state and implemented by private companies, internet service providers or mobile phone companies, or a combination of those. The book argues that internet shutdowns are not legal, necessary or proportional in accordance with international human rights law. Shutdowns intentionally prevent the free flow of information and communication. They disrupt online social, economic and political life. So, each internet shutdown typically violates the fundamental human rights of millions of citizens. This includes their rights to freedom of expression, trade and commerce, democratic debate and civic participation online. Our research looked at case studies from 11 countries between 2016 and 2024. It reveals these shutdowns are timed to coincide with elections or peaceful protests in order to repress political opposition and prevent online reporting. In Senegal five politically motivated shutdowns in just three years transformed the country’s digital landscape. It cut off citizens’ access to online work, education and healthcare information. The Uganda chapter shows how the government imposed social media shutdowns during the election. They were fearful of dissenting voices online including that of musician and politician Bobi Wine. In Ethiopia internet shutdowns are timed to coincide with opposition protests and to prevent live coverage of state violent repression. In Zimbabwe the government cut off the internet in 2019 to quell anti-government demonstrations. It should be a concern that regimes are imposing these digital authoritarian practices with increasing frequency and with impunity. What are the big trends?The report warns that internet shutdowns are being used to retain power through authoritarian controls. Across Africa, governments are normalising their use to suppress dissent, quell protests and manipulate electoral outcomes. These blackouts are growing in scale and frequency from a total of 14 shutdowns in 2016 to 28 shutdowns in 2024. There have been devastating consequences in an ever-more digitally connected world. Internet shutdowns have also increased in sophistication. Partial shutdowns can target specific provinces or websites, so that opposition areas can be cut off. In recent years foreign states, military regimes and warring parties have also resorted to the use of internet shutdown as a weapon of war. This was done by targeting and destroying telecommunications infrastructure. Ethiopia has experienced the most internet shutdowns in Africa – 30 in the last 10 years. They’ve become a go-to tactic of the state in their attempt to silence dissent in the Oromo and Amhara regions. Shutdowns are timed to coincide with state crackdowns on protests or with military actions – preventing live reporting of human rights violations. Ethiopia is a clear example of how internet shutdowns both reflect and amplify existing political and ethnic power interests. Zimbabwe is one of many examples in the book of the colonial roots of shutdowns. The first media shutdowns in Zimbabwe were imposed by the British, who closed newspapers to silence calls for political independence. After liberation, the new government used its own authoritarian control over the media to disseminate disinformation and curtail opposition calls for justice and full democracy. Towards the end of former president Robert Mugabe’s rule, the government imposed a variety of nationwide internet shutdowns. It also throttled the speed of the mobile internet, degrading the service enough to significantly disrupt opposition expression and organisation. Sudan has experienced 21 internet shutdowns in the last decade. These have increased in recent years as the political and military action has intensified. Intentional online disruption has been consistently deployed by the state during protests and periods of political unrest, particularly in response to resistance movements and civil uprisings during the ongoing conflict. Has there been effective resistance to shutdowns?Activists resist by using virtual private network software (VPNs) to disguise their location. Or by using satellite connections not controlled by the government and foreign SIM-cards. They also mobilise offline protests despite violent repression. Nigeria has not suffered the same volume of internet shutdowns as Sudan or Ethiopia. This is partly because civil society is stronger and is able to mount a more robust response in the face of state disruption of the right to free expression. When an internet shutdown has been imposed in Nigeria, the state has not enjoyed the same impunity as the government in Zimbabwe or elsewhere. When Nigerians were unable to work online or participate in the online social and political life of the community, they took decisive action by acting collectively. They selectively litigated against the government. This led to the courts ruling that the internet shutdown was not lawful, necessary or proportionate. The government was forced to lift the ban. How has 2025 fared when it comes to shutdowns?We have seen both positive and negative trends in 2025. The total number of internet shutdowns across the continent continues to grow. The increasing ability of regimes to narrowly target shutdowns on specific areas is of great concern as it allows the state to punish opposition areas while privileging others. On the positive side, we have seen resistance rise: both in terms of the use of circumvention technologies but also in the emerging ability of civil society organisations to stand up to repressive governments. What must happen to prevent shutdowns?The right to work, freedom of expression and association, and the right to access education are fundamental human rights both offline and online. African governments are signatories to both the Universal Convention on Human Rights and to the Africa Union Charter on Human and People’s Rights. Yet, politicians in power too often ignore these commitments to preserve their personal hold on power. In some African countries citizens are now exercising their own power to hold governments to account but this is easier in countries that have strong civil society, independent courts and relatively free media. Even where this is not the case the constitutional court is an option for raising objections when the state curtails fundamental freedoms. And while it is states that order internet shutdowns, it is private mobile and internet companies that implement them. Private companies have obligations to promote and protect human rights. If companies agreed collectively not to contribute to rights violations and refused to impose internet shutdowns, it would be a great leap forward in ending this authoritarian practice. Tony Roberts, Digital Research Fellow, Institute of Development Studies This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Web’s inventor says news media bargaining code could break the internet. He’s right — but there’s a fix (2026-01-07T11:43:00+05:30)

Tama Leaver, Curtin UniversityThe inventor of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, has raised concerns that Australia’s proposed News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code could fundamentally break the internet as we know it. His concerns are valid. However, they could be addressed through minor changes to the proposed code. How could the code break the web?The news media bargaining code aims to level the playing field between media companies and online giants. It would do this by forcing Facebook and Google to pay Australian news businesses for content linked to, or featured, on their platforms. In a submission to the Senate inquiry about the code, Berners-Lee wrote:

Currently, one of the most basic underlying principles of the web is there is no cost involved in creating a hypertext link (or simply a “link”) to any other page or object online. When Berners-Lee first devised the World Wide Web in 1989, he effectively gave away the idea and associated software for free, to ensure nobody would or could charge for using its protocols. He argues the news media bargaining code could set a legal precedent allowing someone to charge for linking, which would let the genie out of the bottle — and plenty more attempts to charge for linking to content would appear. If the precedent were set that people could be charged for simply linking to content online, it’s possible the underlying principle of linking would be disrupted. As a result, there would likely be many attempts by both legitimate companies and scammers to charge users for what is currently free. While supporting the “right of publishers and content creators to be properly rewarded for their work”, Berners-Lee asks the code be amended to maintain the principle of allowing free linking between content. Google and Facebook don’t just link to contentPart of the issue here is Google and Facebook don’t just collect a list of interesting links to news content. Rather the way they find, sort, curate and present news content adds value for their users. They don’t just link to news content, they reframe it. It is often in that reframing that advertisements appear, and this is where these platforms make money. For example, this link will take you to the original 1989 proposal for the World Wide Web. Right now, anyone can create such a link to any other page or object on the web, without having to pay anyone else. But what Facebook and Google do in curating news content is fundamentally different. They create compelling previews, usually by offering the headline of a news article, sometimes the first few lines, and often the first image extracted. For instance, here is a preview Google generates when someone searches for Tim Berners-Lee’s Web proposal: Evidently, what Google returns is more of a media-rich, detailed preview than a simple link. For Google’s users, this is a much more meaningful preview of the content and better enables them to decide whether they’ll click through to see more. Another huge challenge for media businesses is that increasing numbers of users are taking headlines and previews at face value, without necessarily reading the article. This can obviously decrease revenue for news providers, as well as perpetuate misinformation. Indeed, it’s one of the reasons Twitter began asking users to actually read content before retweeting it. A fairly compelling argument, then, is that Google and Facebook add value for consumers via the reframing, curating and previewing of content — not just by linking to it. Can the code be fixed?Currently in the code, the section concerning how platforms are “Making content available” lists three ways content is shared:

Similar terms are used to detail how users might interact with content. If we accept most of the additional value platforms provide to their users is in curating and providing previews of content, then deleting the second element (which just specifies linking to content) would fix Berners-Lee’s concerns. It would ensure the use of links alone can’t be monetised, as has always been true on the web. Platforms would still need to pay when they present users with extracts or previews of articles, but not when they only link to it. Since basic links are not the bread and butter of big platforms, this change wouldn’t fundamentally alter the purpose or principle of creating a more level playing field for news businesses and platforms. In its current form, the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code could put the underlying principles of the world wide web in jeopardy. Tim Berners-Lee is right to raise this point. But a relatively small tweak to the code would prevent this, It would allow us to focus more on where big platforms actually provide value for users, and where the clearest justification lies in asking them to pay for news content. For transparency, it should be noted The Conversation has also made a submission to the Senate inquiry regarding the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code. Tama Leaver, Professor of Internet Studies, Curtin University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Rather Than Taking Jobs in Tech, 2 Young Software Engineers Use Talents to Crush Poaching in India (2026-01-05T13:50:00+05:30)

Indian elephant bull in musth in Bandipur National Park – credit Yathin S Krishnappa CC 3.0. Indian elephant bull in musth in Bandipur National Park – credit Yathin S Krishnappa CC 3.0.Rather than taking their software and programming degrees into the tech sector, two young Kerala men are using them to bring India’s efforts to track, prevent, and punish wildlife crime into the 21st century with a suite of sophisticated apps and tools. They believe they are the first to bring this level of digitization into wildlife conservation, allowing courts to rapidly process wildlife crime cases, rangers to track and analyze patterns of criminal activity in forests, and much more. Paper records, written by hand, recorded by memory, are the kind of data that so many ranger teams and criminal prosecutors of wildlife crime have to rely on around the world in the course of their noble work, and India is no exception. “I realized how there is a gap in the market. There is almost zero technology to track any kind of wildlife crime in India,” said Allen Shaji, co-founder of Leopard Tech Labs. “Working with the Wildlife Trust of India and with their support, our company was able to make HAWK or ‘Hostile Activity Watch Kernel’ with the forest department of Kerala,” he says. Along with his college buddy and fellow cofounder Sobin Matthew, Leopard Tech Labs developed four unique programs now in use by the Kerala Forest Department, called Cyber HAWK, SARPA (Snake Awareness, Rescue and Protection App), Jumbo Radar, and WildWatch. “HAWK is an offense management system that includes case handling, court case monitoring, communication management, and wildlife death monitoring,” Allen told The Better India, explaining that before this, all casework was recorded on papers. Now, HAWK can quickly summarize vast amounts of data into various kinds of digital documents, like a Google spreadsheet, PDF, Microsoft Excel, etc. HAWK can surf the data inputs in seconds, enabling real-time answers to be generated while court or parliament is in session, whether that’s a spreadsheet on the year-over-year rate of elephant deaths, or a police report from the scene of a wildlife crime arrest or trafficking bust. HAWK is not only used by the authorities, but contains big datasets provided by the IUCN, the world’s largest wildlife conservation organization.  Sobin Mathew and Allen Shaji of Leopard Tech Labs – credit Leopard Tech Labs, released to The Better India Sobin Mathew and Allen Shaji of Leopard Tech Labs – credit Leopard Tech Labs, released to The Better IndiaIn addition to HAWK, Jumbo Radar allows the forest departments of India to track elephants in real-time in case they should depart a nature reserve, while WildWatch uses machine learning to predict future incidents of human-wildlife conflict before they happen. In particular, it uses seasonal movements of animals, past records of violence against wildlife, and data on crops including the amount of land cropped, the proximity to nature reserves, and when in the year humans are working on the boundaries of the cropped areas all to predict where conflicts will happen before they do. “This information allows for targeted interventions, such as advising villagers to relocate or alter crop cultivation practices, thereby mitigating conflicts and promoting coexistence,” Allen says. Already Leopard Tech Labs’ products are moving beyond Kerala to Tamil Nadu, and three tiger reserves have begun using their suite of solutions. Leopard Tech has even developed an app for Brazil—to help reduce human-snake conflict.Wildlife trafficking is the third-most lucrative illegal trade in the world, and nations with weak enforcement of environmental laws risk becoming hotbeds for poaching of far more than just elephants and rhinos. Rather Than Taking Jobs in Tech, 2 Young Software Engineers Use Talents to Crush Poaching in India |

What AI earbuds can’t replace: The value of learning another language (2025-12-31T11:51:00+05:30)

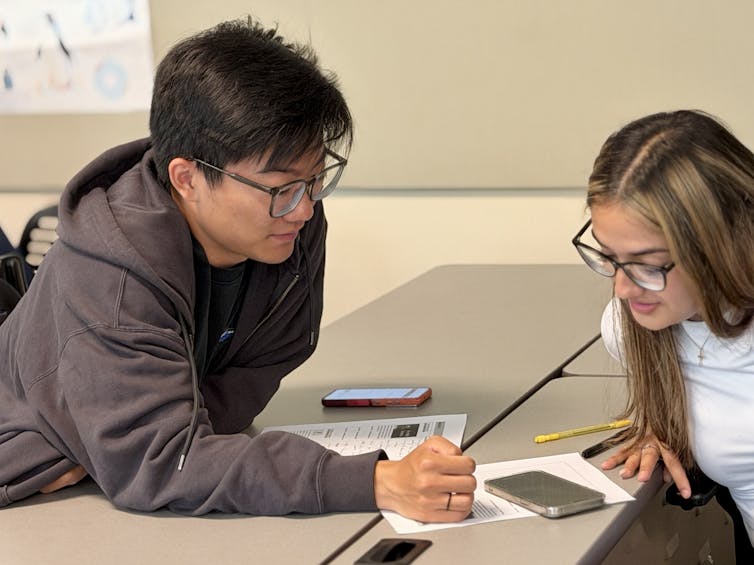

Gabriel Guillén, Middlebury College and Thor Sawin, Middlebury CollegeYour host in Osaka, Japan, slips on a pair of headphones and suddenly hears your words transformed into flawless Kansai Japanese. Even better, their reply in their native tongue comes through perfectly clear to you. Thanks to artificial intelligence, neither of you is lost in translation. What once seemed like science fiction is now marketed as a quick fix for cross-cultural communication. Such AI-powered tools will be useful for many people, especially for tourists or in any purely transactional situation, even if seamless automatic interpretation remains at an experimental stage. Does this mean the process of learning another language will soon be a thing of the past? As scholars of computer-assisted language learning and linguistics, we disagree and see language learning as vital in other ways. We have devoted our careers to this field because we deeply believe in the lasting and transformative value of learning and speaking languages beyond one’s mother tongue. Lessons from past language ‘disruptions’This isn’t the first time a new technology has promised massive disruption to learning languages. In recent years, language learning startups such as Duolingo aimed to make acquiring a language easier than ever, in part by gamifying language. While these apps have certainly made learning more accessible to more people, our research shows most platforms and apps have failed to fully replicate the inherently social process of learning a language. The meaning of learning a languageNumbers aside, the gold standard of language learning is the ability to follow and contribute to a live group conversation. Since World War II, government departments and education programs recognized that text-centered grammar-translation methods did little to support real interaction. Interpersonal conversational competence gradually became the main goal of language classes. While technologies you can put in your ear or wear on your face now promise to revolutionize interpersonal interaction, their usefulness in such conversations actually falls along a spectrum. At one end, you have simple tasks you have to navigate while visiting a city where they speak a different language, like checking out of a hotel, buying a ticket at a kiosk or finding your way around town. That is, people from different backgrounds working together to achieve a goal – a successful checkout, a ticket purchase or getting to the famous museum you want to visit. Any mix of languages, gestures or tools – even AI tools – can help in this context. In such cases, where the goal is clear and both parties are patient, shared English or automated interpretation can get the job done while bypassing the hard work of language learning. At the other end, identity matters as much as content. Meeting your in-laws, introducing yourself at work, welcoming a delegation or presenting to a skeptical audience all involve trust and social capital. Humor, idioms, levels of formality, tone, timing and body language shape not just what you say but who you are. The effort of learning a language communicates respect, trust and a willingness to see the world through someone else’s eyes. We believe language learning is one of the most demanding and rewarding forms of deep work, building cognitive resilience, empathy, identity and community in ways technology struggles to replicate. The 2003 movie “Lost in Translation,” which depicts an older American man falling in love with a much younger American woman, was not about getting lost in the language but delved into issues of interculturality and finding yourself while exposed to the other. Indeed, accelerating mobility due to climate migration, remote work and retirement abroad all increase the need to learn languages – not just translate them. Even those staying in place often seek deeper connections through language as learners with familial and historical ties.  A Spanish learner from China negotiates meaning with an English learner from Mexico in California. Gabriel Guillén, 2025, CC BY-SA A Spanish learner from China negotiates meaning with an English learner from Mexico in California. Gabriel Guillén, 2025, CC BY-SAWhere AI falls shortThe latest AI technologies, such as those used by Apple’s newest AirPods to instantly interpret and translate, certainly are powerful tools that will help a lot of people interact with anyone who speaks a different language in ways previously only possible for someone who spent a year or two studying it. It’s like having your own personal interpreter. Yet relying on interpretation carries hidden costs: distortion of meaning, loss of interactive nuance and diminished interpersonal trust. An ethnography of American learners with strong motivation and near limitless support found that falling back on speaking English and using technology to aid translation may be easier in the short term, but this undercuts long-term language and integration goals. Language learners constantly face this choice between short-term ease and long-term impact. Some AI tools help accomplish immediate tasks, and generative AI apps can support acquisition but can take away the negotiations of meaning from which durable skills emerge. AI interpretation may suffice for one-on-one conversations, but learners usually aspire to join ongoing conversations already being had among speakers of another language. Long-term language learning, while necessarily friction-filled, is nevertheless beneficial on many fronts. Interpersonally, using another’s language fosters both cultural and cognitive empathy. In addition, the cognitive benefits of multilingualism are equally well documented: resistance to dementia, divergent thinking, flexibility in shifting attention, acceptance of multiple perspectives and explanations, and reduced bias in reasoning. The very attributes companies seek in the AI age – resilience, lifelong learning, analytical and creative thinking, active listening – are all cultivated through language learning. Rethinking language education in the age of AISo why, in the increasingly multilingual U.K. and U.S., are fewer students choosing to learn another language in high school and at university? The reasons are complex. Too often, institutions have struggled to demonstrate the relevance of language studies. Yet innovative approaches abound, from integrating language in the contexts of other subjects and linking it to service and volunteering to connecting students with others through virtual exchanges or community partners via project-based language learning, all while developing intercultural skills. So, again, what’s the value of learning another language when AI can handle tourism phrases, casual conversation and city navigation? The answer, in our view, lies not in fleeting encounters but in cultivating enduring capacities: curiosity, empathy, deeper understanding of others, the reshaping of identity and the promise of lasting cognitive growth. For educators, the call is clear. Generative AI can take on rote and transactional tasks while excelling at error correction, adapting input and vocabulary support. That frees classroom time for multiparty, culturally rich and nuanced conversation. Teaching approaches grounded in interculturality, embodied communication, play and relationship building will thrive. Learning this way enables learners to critically evaluate what AI earbuds or chatbots create, to join authentic conversations and to experience the full benefits of long-term language learning. Gabriel Guillén, Professor of Language Studies, Middlebury College and Thor Sawin, Professor of Linguistics, Middlebury College This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Coupang unveils $1.17 billion compensation plan over data breach (2025-12-31T11:50:00+05:30)

|

IANS Photo Seoul, December 29 (IANS): E-commerce giant Coupang announced a compensation plan worth more than 1.68 trillion won ($1.17 billion) on Monday following a massive personal data breach. The compensation plan comes a day after Coupang founder Kim Bom-suk issued his first public apology since the incident, which affected nearly two-thirds of South Korea's population, reports Yonhap news agency. Under the plan, the U.S.-listed company will provide 50,000 won worth of discounts and coupons to each of 33.7 million customers, including paid Coupang Wow members, regular users and former customers who have closed their accounts, the company said in a press release. Compensation payments will be made gradually starting Jan. 15, it added. "Taking this incident as a turning point, Coupang will wholeheartedly embrace customer-centric principles and fulfill its responsibilities to the very end, transforming into a company that customers can trust," Coupang's interim Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Harold Rogers said in the release. The per-person compensation consists of 5,000 won for Coupang's e-commerce platform, 5,000 won for food delivery service Coupang Eats, 20,000 won for Coupang's travel products and 20,000 won for R.LUX luxury beauty and fashion products. Last week, Coupang said it had identified a former employee responsible for the data leak through forensic evidence, recovered the equipment used in the hacking and received a confession from the suspect. The company claimed that data from only about 3,000 accounts was actually saved and later deleted by the suspect. The government, however, has dismissed Coupang's findings as a "unilateral claim," noting that a joint public-private investigation into the incident has yet to release any conclusions. On November 29, Coupang confirmed that the personal information of 33.7 million customer accounts had been exposed, far exceeding the 4,500 accounts initially reported to authorities on Nov. 20. Given that active users of Coupang's product commerce division, including its delivery service, reached 24.7 million in the third quarter, the scale of the breach suggests that nearly the entire user base may have been affected.The company said the compromised data included users' names, phone numbers, email addresses and delivery addresses. Coupang unveils $1.17 billion compensation plan over data breach | MorungExpress | morungexpress.com |

Armenian authorities charge 11 in transnational cybercrime case (2025-12-30T13:42:00+05:30)

The Armenian Investigative Committee has charged 11 people, including Armenian and foreign nationals, over their roles in a transnational criminal organization involved in large-scale cyber theft. The Special Investigations Department of the Investigative Committee said on Tuesday the group was formed in November 2018 and operated until March 11, 2025, using a hierarchical structure and specialized roles. Members posed as lawyers, representatives of international companies, cryptocurrency platforms and financial officers to carry out the cyber thefts from rented offices.Six of the accused face charges of participating in a criminal organization and committing particularly large-scale computer theft, while the remaining five face similar charges. The case has been sent to the supervising prosecutor with an indictment. custom title |

Britney Spears returns to Instagram, talks about 'boundaries' (2025-12-24T12:45:00+05:30)

(Photo: Britney Spears/Instagram) IANS Los Angeles, (IANS) Popstar Britney Spears has made a comeback on social media weeks after appearing to deactivate her account amid a spat with her ex-spouse Kevin Federline. After a string of erratic posts and a public clash with her former husband, Kevin Federline, the 43-year-old singer appeared to deactivate her account earlier on November 2, with her page showing a message that it “may have been removed”. Returning to Instagram, the Toxic hitmaker reflected on her "crazy" year and encouraged her followers to build "boundaries,” reports femalefirst.co.uk. Alongside a screenshot of one of her videos in a racy ensemble, she wrote: “So much has happened this year, it’s crazy … I try to live within my means and the book, ‘Draw the Circle’ is an incredible perspective. “Get your ballerina, circle, and own your boundaries. It’s incredibly strict and somewhat of a form of prayer but with so many endless possibilities in life, it’s important to do you and keep it simple. I know there is a confusing side too. The devil is in the details but we can get to that later (sic)" Fans have shown concern since the singer shared clips of herself dancing with visible bruises on her arms and cryptic captions about her sons, Sean Preston, 20, and Jayden James, 19. In one post, Spears appeared in a plunging pink swimsuit and knee-high black boots, posing in front of a mirror in her Los Angeles home. The background showed piles of clothes on the floor, prompting renewed discussion about her wellbeing. In another clip last month, she revealed a “horrible” leg injury, explaining she had “fell down the stairs” and her leg “snaps out now and then”. She said: “Not sure if it’s broken but for now it’s snapped in!!! Thank u god.”Britney captioned the same video with a message referencing her faith and her children, saying: “My boys had to leave and go back to Maui… this is the way I express myself and pray through art… father who art in heaven… I’m not here for concern or pity, I just want to be a good woman and be better… and I do have wonderful support, so have a brilliant day !!!” Britney Spears returns to Instagram, talks about 'boundaries' | MorungExpress | morungexpress.com |

The social media ban is just the start of Australia’s forthcoming restrictions – and teens have legitimate concerns (2025-12-22T12:39:00+05:30)

Giselle Woodley, Edith Cowan University and Paul Haskell-Dowland, Edith Cowan UniversityThere has been massive global interest in the new social media legislation introduced in Australia aimed at protecting children from the dangers of doom‑scrolling and mental‑health risks potentially posed by these platforms during their developmental years The platforms’ methods so far for verifying young people’s ages have shown mixed effectiveness. The Australian Christmas period may be interrupted with cries of “I’m so bored without Insta”, but the Australian government is not done yet. New measures are scheduled to come into force before the new year, which will include further restrictions on content deemed age-inappropriate across a range of internet services. What are the new restrictions?While families grapple with the social media ban, Australia is about to dial up the volume on increased measures to further regulate the internet through the impending industry codes. These will eventually be implemented across services including search engines, social media messaging services, online games, app distributors, equipment manufacturers and suppliers (smartphones, tablets and so on) and AI chatbots and companions. Over the Christmas break we’ll start to see hosting services (and ISPs/search engines) that deliver sexual content including pornography, alongside material categorised as promoting eating disorders and self-harm, start to impose various restrictions, including increased age checks. However, there are concerns the codes may result in overreach, affecting marginalised communities and limiting young people’s access to educational material. After all, big tech doesn’t have a great track record, particularly in terms of sexual health material and associated educational content. How will it work?From December 27 (with some measures coming in later), sites delivering content that fall under the new industry codes will be required to implement “appropriate age assurance”. How they will do this is largely left to the providers to decide. Age checks will likely be administered across the internet through various age-assurance and age-verification processes to limit young people’s access. While much of the media coverage has focused on the social media ban, the industry codes have been much quieter, and arguably more difficult to understand. Discussion has focused on the impact and extent of the code with little focus on the very people that the changes are designed to impact: young people. The quiet voicesOur new research explores the view of Australia’s teens on various age-verification and age-assurance measures – views that don’t appear to have been fully taken into consideration by policymakers. Teens believe governments and industry should be “doing more” to make online spaces safer, but are sceptical about age verification measures. Unsurprisingly, consistent with other research, teens confess they will find ways around the ban, such as the use of VPNs, borrowed ID or using images of adults to overcome age verification and assurance measures. Biometric measures such as facial identification have also shown concerning racial, gender and age bias. Miles, 16, told us:

Much like adults, teens held concerns around the privacy and security implications of age verification. Some measures require personal data to be either validated or processed by third-party companies, potentially outside Australia. Users are expected to trust such companies despite data being a highly valuable commodity in the modern age. Previous research has indicated scepticism around the safety of allowing third parties to host such personal data. This raises justified security and privacy concerns for all Australian users – especially following the recent Discord data leak that disclosed photos used for age verification of Australian account holders. Even research by the office of the eSafety commissioner itself indicates teens are tech-savvy and likely to bypass restrictions. In the United Kingdom (where on the day of implementation, one VPN platform saw a 1,400% surge in uptake, minors are now using unstable free VPNs to overcome Ofcom’s age-assurance measures to access blocked pornographic content. While functional for the end-user, their use leaves them susceptible to sensitive personal data leaks and phishing, further compromising their safety. Such concerns are exacerbated by uncertainty over the kind of data being captured by third parties and government bodies, (particularly if digital ID or temporary digital tokens are to be used as a measure in future). For teens, this possibility was of particular concern when considering access to online sexual content as the new rules come into force. As Miles told us:

Teens note that by restricting access to content, the government may actually be making the desire to access content more enticing too. Some may even see it as a challenge to find ways around the restrictions. Tiffany, 16, told us:

More relevant measures than ageInterestingly, some teens suggest that maturity would be a better measure of emotional and cognitive readiness for content than age. Tiffany put it this way:

However, they conceded this would be very difficult to measure. Teens were supportive of protections for younger children consistent with New Zealand research. Levi (pre-teen) said:

However, they also argue that for older teens there may be benefit to accessing both sexual content and social media for educational purposes, particularly for sexual information. Teens argue that independence and autonomy is key in these crucial years of development as emerging adults. Tiffany said

Many participants stressed they are able to self-regulate. Arguably, teens will inevitably access content, whether it be social media or sexual content online, and benefit from chances to build these skills. What lessons need to be learned?Such measures often overlook young people’s fundamental rights, including their sexual rights, and policymakers need to consider the views of young people themselves. Until recently, these views have been strikingly absent from these debates but represent valuable contributions that should be appropriately considered and integrated into future plans. Findings indicate there is a growing need to separate older teens from children in policy. Teens also overwhemingly recognised education (including digital literacy and lessons relating to sexual health and behaviours) in offline and online spaces as powerful tools – that should not be withheld or restricted unnecessarily. Giselle Woodley, Lecturer and Research Fellow, Edith Cowan University and Paul Haskell-Dowland, Professor of Cyber Security Practice, Edith Cowan University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Social media, not gaming, tied to rising attention problems in teens, new study finds (2025-12-19T11:13:00+05:30)

|

Torkel Klingberg, Karolinska Institutet and Samson Nivins, Karolinska Institutet The digital revolution has become a vast, unplanned experiment – and children are its most exposed participants. As ADHD diagnoses rise around the world, a key question has emerged: could the growing use of digital devices be playing a role? To explore this, we studied more than 8,000 children, from when they were around ten until they were 14 years of age. We asked them about their digital habits and grouped them into three categories: gaming, TV/video (YouTube, say) and social media. The latter included apps such as TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, X, Messenger and Facebook. We then analysed whether usage was associated with long-term change in the two core symptoms of ADHD: inattentiveness and hyperactivity. Our main finding was that social media use was associated with a gradual increase in inattentiveness. Gaming or watching videos was not. These patterns remained the same even after accounting for children’s genetic risk for ADHD and their families’ income. We also tested whether inattentiveness might cause children to use more social media instead. It didn’t. The direction ran one way: social media use predicted later inattentiveness. The mechanisms of how digital media affects attention are unknown. But the lack of negative effect of other screen activities means we can rule out any general, negative effect of screens as well as the popular notion that all digital media produces “dopamine hits”, which then mess with children’s attention. As cognitive neuroscientists, we could make an educated guess about the mechanisms. Social media introduces constant distractions, preventing sustained attention to any task. If it is not the messages themselves that distract, the mere thought of whether a message has arrived can act as a mental distraction. These distractions impair focus in the moment, and when they persist for months or years, they may also have long-term effects. Gaming, on the other hand, takes place during limited sessions, not throughout the day, and involves a constant focus on one task at a time. The effect of social media, using statistical measures, was not large. It was not enough to push a person with normal attention into ADHD territory. But if the entire population becomes more inattentive, many will cross the diagnostic border. Theoretically, an increase of one hour of social media use in the entire population would increase the diagnoses by about 30%. This is admittedly a simplification, since diagnoses depend on many factors, but it illustrates how even an effect that is small at the individual level can have a significant effect when it affects an entire population. A lot of data suggests that we have seen at least one hour more per day of social media during the last decade or two. Twenty years ago, social media barely existed. Now, teenagers are online for about five hours per day, mostly with social media. The percentage of teenagers who claim to be “constantly online” has increased from 24% in 2015 to 46% 2023. Given that social media use has risen from essentially zero to around five hours per day, it may explain a substantial part of the increase in ADHD diagnoses during the past 15 years. The attention gapSome argue that the rise in the number of ADHD diagnoses reflects greater awareness and reduced stigma. That may be part of the story, but it doesn’t rule out a genuine increase in inattention. Also, some studies that claim that the symptoms of inattention have not increased have often studied children who were probably too young to own a smartphone, or a period of years that mostly predates the avalanche in scrolling. Social media probably increases inattention, and social media use has rocketed. What now? The US requires children to be at least 13 to create an account on most social platforms, but these restrictions are easy to outsmart. Australia is currently going the furthest. From December 10 2025, media companies will be required to ensure that users are 16 years or above, with high penalties for the companies that do not adhere. Let’s see what effect that legislation will have. Perhaps the rest of the world should follow the Australians. Torkel Klingberg, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet and Samson Nivins, Postdoctoral Researcher, Women's and Children's Health, Karolinska Institutet This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Caregiver smartphone use can affect a baby’s development. New parents should get more guidance (2025-12-17T11:27:00+05:30)

Miriam McCaleb, University of CanterburyWe already know excessive smartphone use affects people’s mental health and their relationships. But when new parents use digital technologies during care giving, they might also compromise their baby’s development. Smartphone use in the presence of infants is associated with a range of negative developmental outcomes, including threats to the formation of a secure attachment. The transition into parenthood is an ideal time for healthy behaviour change. Expectant parents see a range of professionals, but as we found in our new study, they don’t receive any co-ordinated support or advice on managing digital devices in babies’ presence. One of the new mums we interviewed said:

Another participant said:

Adult smartphone use is not mentioned in well-child checks. We argue this is a missed public health opportunity. Secure attachment is important for a baby’s development. They need hours of gazing at their families’ faces to optimally wire their brains. This is more likely when the parent is sensitive to a baby’s cues and emotionally available. But ubiquitous smartphone use by caregivers has the potential to disrupt attachment by interrupting this sensitivity and availability. Babies’ central nervous system and senses are immature. But they are born into a rapidly moving world, filled with voices and faces from digital sources. This places a burden on caregivers to act as a human filter between a newborn’s neurobiology and digital distractions. Disrupting relationshipsPsychologists have described the phenomenon of frequent disruptions and distractions during parenting – and the disconnection of the in-person relationship – as “technoference”. A caregiver’s eyes are no longer on the infant but on the device. Their attention is gone, in a state described as “absent presence”, and the phone becomes a “social pollution”. It’s unpleasant for anyone on the other side of this imbalance. But for babies, whose connection to their significant adults is the only thing that can make them feel safe enough to learn and grow optimally, it causes disproportionate harm because of their vulnerable developmental stage. During the rapid phase of brain growth in infancy, babies are wired to seek messages of safety from their caregiver’s face. Smartphone use blanks caregivers’ facial expressions in ways that cause physiological stress to babies. When a caregiver uses their phone while feeding an infant, babies are more likely to be overfed. The number of audible notifications on a parent’s device relates to a child’s language development, with more alerts associated with fewer words at 18 months. If that’s not reason enough to reign in phone use, evidence also shows that smartphone use can be a source of stress and guilt for parents. This suggests parents themselves would benefit from more purposeful and reduced smartphone habits. Some public health researchers are urging healthcare workers to consider the parent-infant relationship in addition to the respective health of the baby and caregiver themselves. This relational space between people is suffering as a result of the social pollution of smartphone-distracted care. Babies’ brains grow so fast, we mustn’t let this process be compromised by the distraction of the attention economy. Our research shows new parents could use information and support around the use of digital devices. We also recommend that other family members modify their smartphone habits around a new baby. Whānau can create a family media plan and make sure they have someone to talk to about this issue. Health policies should focus on early investment in parents and children, by prioritising education and action on smartphone use around babies. This would benefit the wellbeing of new parents and the lifelong development of infants. Miriam McCaleb, Fellow in Public Health, University of Canterbury This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |